How God Comes to Speak Through a Toad

The Creative Genius Flowing Through Dylan and Kendrick and Homer

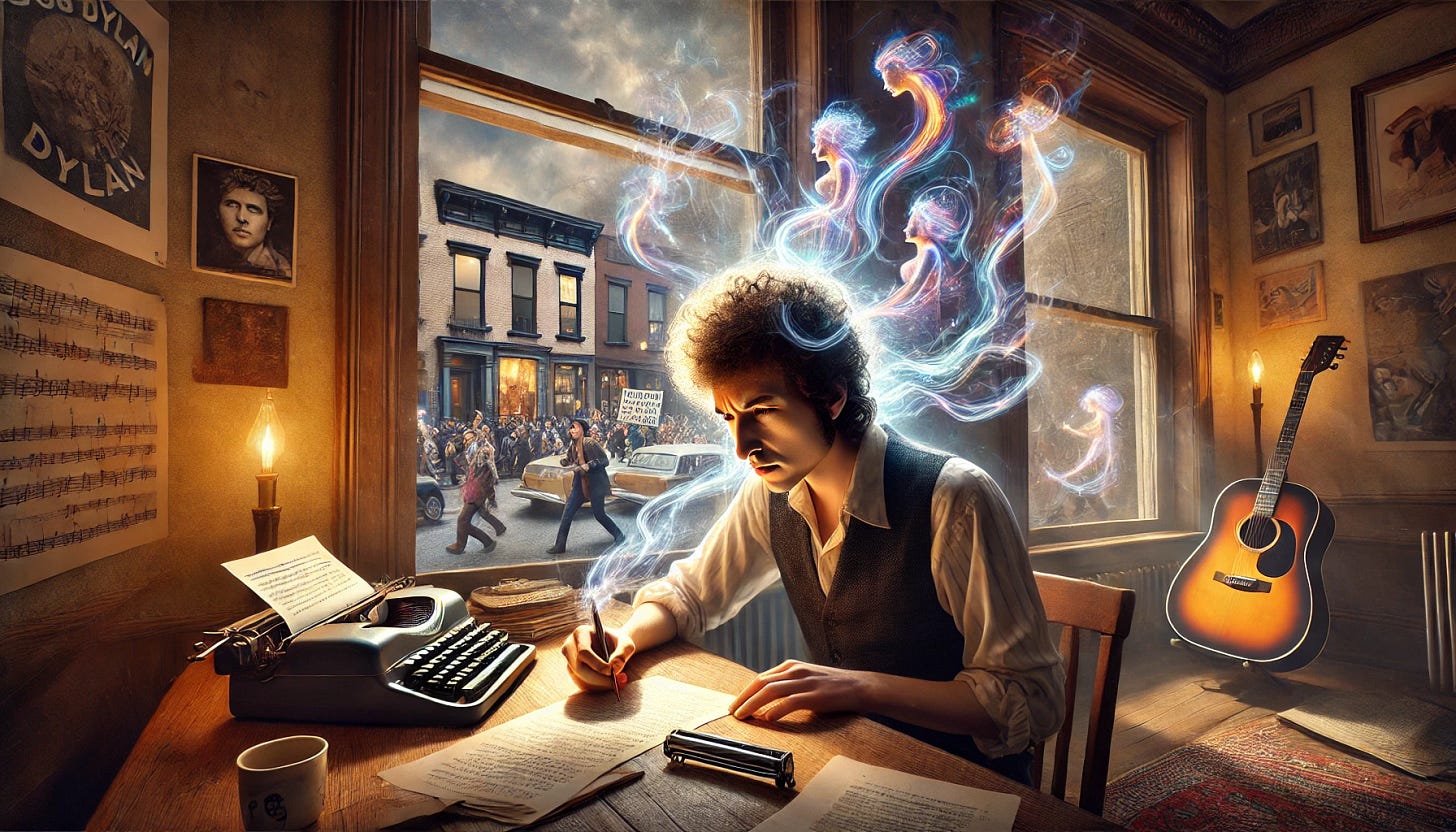

I recently watched the new Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothy Chalamet and had a pretty good time. The movie stirred some old thoughts about Dylan’s life and I thought I’d share.

I’ve always been a fan of Bob Dylan. I rediscovered him in college, and saw his early folk music as poetry. In fact, all music I had come to appreciate up until that time was the lyrical stuff, and most of it had been hip hop. Dylan was an exception.

And the more I dug into Bob Dylan’s biography, the more interesting he became as a creative figure.

People were often surprised by him in his early career. He seemed like an unlikely person to rally a nation in the 60s, a time of social upheaval for America.

Joan Baez, Dylan’s onetime lover and famous singer in her own right, said she was blown away upon hearing Dylan sing “With God on Our Side.” She said, “I never thought anything so powerful could come out of that little toad.”

“Toad” does feel fitting, as Bob Dylan does kind of croak when he sings, and I’m sure he cut even less of an imposing figure as a scrawny 20-year-old kid. But this toad is also the only songwriter to have won a Nobel Prize in Literature. So how did Bob Zimmerman become the great Bob Dylan? And more importantly, how did he capture lightning in a bottle in the 60s?

As his biopic alludes to, Dylan was a master of creative invention. His muse captured his spirit from a young age and drove him, at age 19, from rural Minnesota to buzzing New York where he quickly became a bohemian activist, folk hero, counterculture icon.

In a 2004 60 Minutes interview (Dylan’s first televised interview in nearly 20 years), he opens up about some of the mysteries of his creativity.

When asked about one of his classic songs, he says “it came from that wellspring of creativity… I don’t know how I got to write those songs… those early songs were almost magically written… there’s a magic to that… a different kind of penetrating magic, and I did it at one time.”

The interviewer goes on to ask, “You don’t think you can do it today?” and Dylan shakes his head no.

I’ve watched these clips many times and Dylan’s answer always fascinated me. On the one hand, there is the pure genius that Dylan recognizes in his own writing, and then there is the sad truth that Dylan understands that he can’t replicate it. He knows deep down that it was never purely in his control, to channel as he wanted.

Yeesh. I know athletes typically peak in their late twenties, but a musician? But a creative mind? Why does Dylan accept such limits for himself?

I think about creativity often: how to nurture it, how to discover it, how to capture it, how to find a sustainable relationship to it.

In creative industries like film, when your living depends on your creative productivity, it’s hard to accept that your most productive and fruitful creative work can come at unexpected times. That you don’t necessarily clock in and out, or that even when you do, nothing is guaranteed to happen.

The magic of Dylan in the 60s was really a confluence of his musicial spirit, his youthful idealism, and his musical talents (or maybe more importantly, his literary talents). Just as important, you might argue, was the zeitgeist. As the new biopic shows, Dylan was a young upstart in an aging folk scene. He refreshed the tradition and brought a sharp subversion and rebellion to a genre that felt somewhat rustic and prosaic. The movie pays homage to this as Dylan comments to Joan Baez, wondering if her songs all have to be about flowers (or something to that effect). Of course Dylan resonated with Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger for their political and social leanings, but Dylan’s music was much more pointed, and that’s what a divided public was hungry for.

Dylan moved to New York in January of 1961, “a complete unknown,” and by October of that year, he was signed to Columbia Records. Talk about right place right time.

Another one of my favorite voices who speaks about the creative spirit is author Elizabeth Gilbert. Gilbert wrote a book called Big Magic about her relationship to creativity. She had freakish success when her book Eat, Pray, Love became a bestseller and skyrocketed her to literary fame. While she was overjoyed at her success, she was also worried she would live in the shadow of her book’s success her entire life and never measure up.

Lighting had struck for Gilbert, but she didn’t just want a writing perfect storm. She wanted a writing career and so she writes about working to cultivate those perfect storm conditions throughout her life to recreate the genius of her first book.

She writes in Big Magic:

Most of my writing life consists of nothing more than unglamorous, disciplined labor… but sometimes, when I’m in the midst of writing, I feel like I am suddenly walking on one of those moving sidewalks that you find in a big airport terminal; I still have to slog to my gate, and my baggage is still heavy, but I can feel myself being gently propelled by some exterior force. Something is carrying me along—something powerful and generous— and that something is decidently not me… in such instances I write like I am not quite myself. I lose track of time and space and self.

It’s kind of an uncanny thing, but personally, after two decades of various forms of creative practice, I feel I know what Gilbert refers to.

I wrote lots of poetry as a teenager, and in those early stages of my creative self, I always looked back on my writing the next day and wondered, “Did I really write that?” It would come to me in a mad rush in the moment, and it was often messy and needed revision, but little phrases and lines felt like they were almost written in a voice that wasn’t my own. I wondered what I was channeling, or who I was channeling. Now I wonder less, and just lean blissfully into the feeling. It doesn’t matter. Someone or something is carrying me, and I just need to do my part and record faithfully. I’m more scribe than author in those moment, and I feel like a great weight is lifted off of my shoulders.

There’s a line about this from Kendrick Lamar that comes back to me. It’s from his fictional interview with Tupac for the song “Mortal Man” at the end of his album To Pimp a Butterfly.

Kendrick says, “Sometimes, I can get behind a mic and I don’t know what type of energy I’ma push out or where it comes from, trip me out sometimes…”

And Tupac responds (clipped from an old interview), “Because it's spirits. We ain’t even really rappin, we just letting our dead homies tell stories for us.”

Big Magic. Penetrating Magic. Spirits. Muses. Ghosts. Whatever it is, it’s clearly the lifeblood of some of the greatest artists ever.

A recent tattoo I got was a dedication to The Odyssey, the single most influential creative work in my life, and the book’s opening lines are seared into my brain after having read more than 5 translations of the ancient poem:

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story of that man skilled in all ways of contending, the wanderer.”

Sing IN me, Muse. Homer opens his long story not by invoking his own talent and abilities (unlike Snoop here), but by calling to a higher power to help him tell the epic of Odysseus. It’s no task for mere humans, after all.

And I feel when I read some of Elizabeth Gilbert’s words, they are words I could have written myself.

She writes in Big Magic,

“All I know for certain is that this is how I want to spend my life—collaborating to the best of my ability with forces of inspiration that I can neither see, nor prove, nor command, nor understand. It’s a strange line of work, admittedly. I cannot think of a better way to pass my days.”